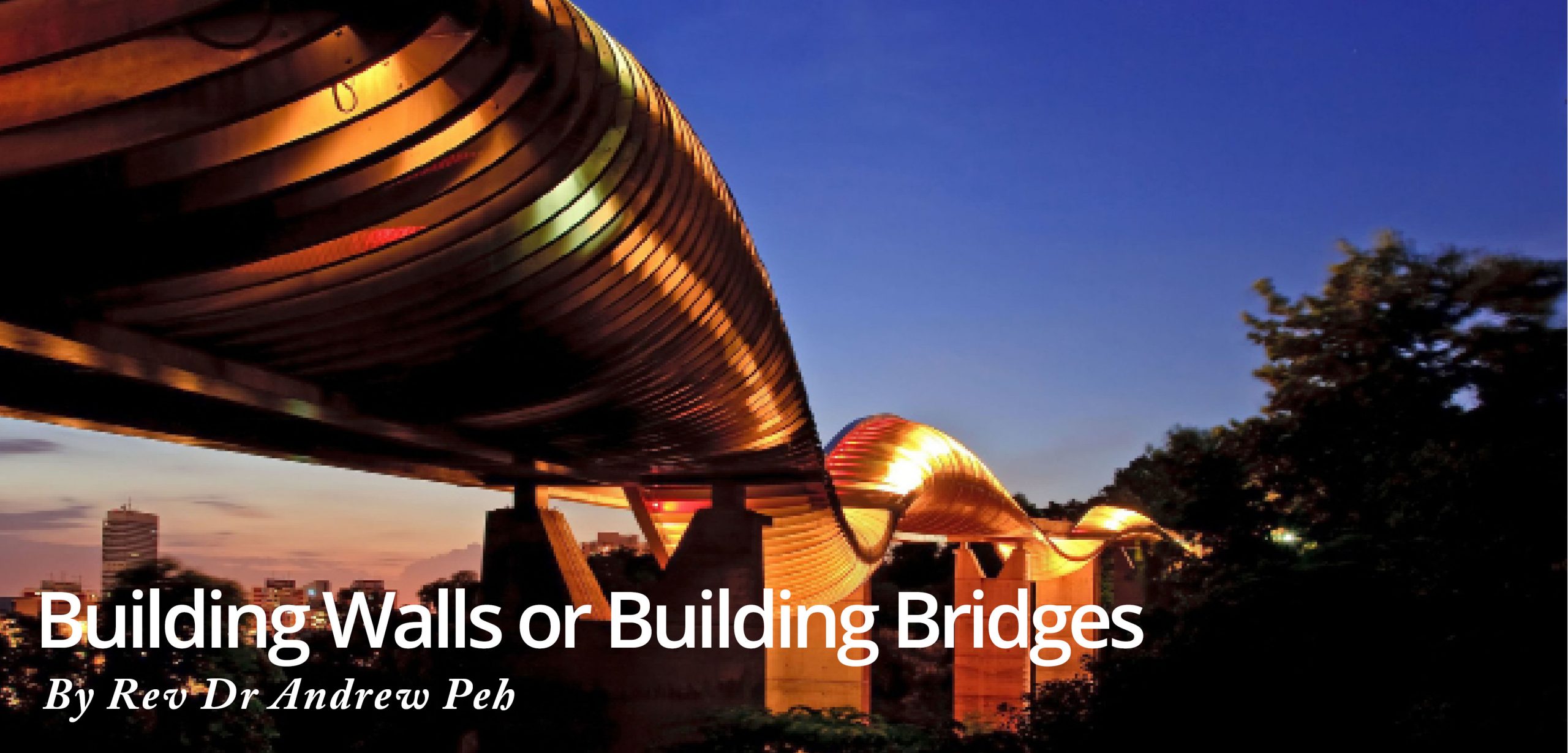

We are inundated with news about a president who is desirous of building a wall to keep the ‘undesirable’ immigrants out of his country. Nearer home, we read of the Rohingyas, a displaced (and despised) people, without a place to call home. And in Singapore, the total number of foreign workers as of 2018 stands at about 1.37 million, according to the Ministry of Manpower.

These are snapshots of the reality of the displacement and migration of peoples. This global diaspora is changing the way we look at the world and the impact and implications are numerous. Missiologists have termed this development ‘diaspora mission’ . There is increasing awareness that mission in our contemporary world is no longer unilinear (from the global north to the global south), but polycentric; that is, we are invited to partner in God’s mission ‘from everywhere to everywhere’.

The biblical basis for diaspora mission is also evident in both the Old and New Testaments. For me, Philip’s encounter with and baptism of the Ethiopian eunuch is one of the most poignant passages. Discounting their ethnic, social and even gender differences, what Philip did in obediently sharing the Good News with the eunuch provides a basis for us to engage those who exist on the periphery of the dominant culture. Justo Gonzalez is right in noting that in the baptism of this eunuch, Philip is doing much more than we think: he is fulfilling the words of the prophet Isaiah, that the eunuch and the foreigner (the Gentiles) also have a place in the house of the Lord.

How do we understand a passage like this? What lessons can we glean? Perhaps the most primary is that God feels passionately about the person on the other side of the wall that we have erected to keep out!

It is significant that the story of Philip encountering the Ethiopian eunuch is placed here in Acts 8. It is Luke’s way of saying that at the moment when the Gospel is reaching to the wider world, wherever you go, whatever culture you come to, whatever situation of human need, sin, exclusion, or oppression you may find, the message of Jesus transcends all – God’s love transcends geography, culture, gender, race, and all the sins that we see in others. We are compelled always to point them to Jesus; because He is the one who brings forgiveness, healing and transformation. Like Jesus, we, the church, should be in the business of demolishing prejudices.

It is said that Singapore is the place where the world converges, and while there have been increased efforts among Singapore churches to send out missionaries, there is also the fact of peoples migrating to Singapore in the hope of a better life, that churches need to give more thought to. This is mission at our doorsteps.

Have churches given sufficient thought of what or how this mission looks like? Do we set up a migrant workers ministry to demonstrate our obedience to God’s missionary mandate while erecting walls of division and disunity, based upon ethnic and cultural differences? Is the Gospel we share indicative of the fact that the God we worship is the One who desires the salvation of all the nations and all of creation?

Diaspora mission enables us to have a view of mission from the perspective of those who are on the margins of our society, just as Philip’s obedience to the Spirit’s leading enables him,to reach out to one who was ethnically, socially, culturally different from him with the saving knowledge of God. Dare we move out from our comfortable middle-class church community to minister amongst the construction workers from India and Bangladesh, the domestic helpers from Myanmar and Indonesia, the nurses from the Philippines, the bus captains and waitresses from China? Dare we be inclusive in our outreach to the ex-offenders, the single parents, the disenfranchised not only by drawing them into the church community but also ensuring that there is no safe distance between ‘them’ and ‘us’?

Dr Goh Wei Leong, one of the founders of HealthServe, shared his story of how he and some like-minded friends initiated a work among migrant workers to provide some basic healthcare for them. They found a place for a clinic in Geylang Lorong 23 and opened it on Saturday afternoons. But to their dismay, not many workers turned up. He was told that if he really wanted to reach out to the migrant workers, he needed to get to the other side of Geylang, to the even-numbered streets where sex workers ply their trade and where many migrant workers live above brothels, where rental rates were cheaper. They subsequently relocated their clinic to the other side of Geylang. For me, this is the true “crossover” project because Dr Goh and his friends took that bold step, like Jesus, to break down the walls of division and cross over to reach out to those who need His touch. “By crossing the street, we crossed over to the side of the vulnerable and oppressed…. We spent many evenings talking to them, telling them about the clinic. And after that, they started coming. It was a major lesson for us; we had to move into their community,” Dr Goh shared.

The urban context of mission is ‘from everywhere to everywhere’. God still calls some to minister in a cross-cultural context as a long-term missionaries, but for the rest of us, God is perhaps calling us to do His work across the road, on the other side and perhaps even in our own homes where we have erected high walls of exclusion instead of bridges of embrace.

What are the bridges that we need to build in place of these walls of exclusion? I recognize that tearing down walls and building bridges will not be easy for the church. It will certainly be uncomfortable; it will challenge our status quo and cause us to consider where/who is at the centre of our church and who is at the centre of our faith. But in keeping with the thrust of the mission of God, we cannot afford to let class, race, gender, politics, geography, culture or any other differences and prejudices hinder us from being an instrument for God’s work. Will you raise a wall or will you build a bridge?

TRUMPET | Cover Story | Apr 2019